Tours of estates like Dougaldston, St John, or River Antoine and Belmont, St Patrick today will reveal little to nothing of slavery unless one has knowledge of what took place here beyond the cocoa trees, sugar-cane fields, and old waterwheel technology that dates to the 18th and 19th centuries (Figures 1, 2). There were no family heirlooms to pass down, no shackles or whips that tell of the brutality, no memory of tears that tell of the suffering, no ruins of thatched houses that reveal the hearth of everyday (enslaved) lives, no drums beating out rhythms of melancholy melodies, no cultural artifacts that linger in museums, and no monuments that sing praises to heroic ancestors. It is a landscape and heritage barren of slavery except in the enduring nightmare of it all.

The current relic landscape, particularly the plantations, reveals little of its slave past. The most noticeable are the few remaining “estate houses” or ruins that may tell a tale of the slave-owning families who resided there, but most were actually built post-Emancipation, having little or no connection to slavery itself. The decaying windmill towers, copper pots, rusted waterwheels and crumbling aqueducts that fueled centuries of production of sugar seem almost out of place today and little connected to that dark past (Figure 2). That brutal, dehumanizing system of forced and torturous servitude that ended 187 years ago. For the majority of Grenadians, the descendants of the islands’ enslaved, there is nothing in these idyllic, picturesque landscapes that reminds of the suffering their ancestors endured during slavery and that impact their lives even today. It is as if slavery never existed at all, or simply vanished with the changing landscape!

But Grenadians have nonetheless found at least three dark corners tucked into the architectural landscape that they have deemed places of significance in the enslavement of their ancestors. On the Hermitage and Mount Rich Plantations in St Patrick and on Melville Street in St George’s, they have identified what have become known as “Slave Pens” where many believe that enslaved Africans were held there for either security, punishment, breeding, or any variety of nefarious purposes. The cavernous and dark nature of these spaces signify to many the depravity of slavery, and have made these places reverential to the memory of brutalized lives. They are akin to tombs of the unknown to countless ancestors who we know so little of beyond a singular name, if at all. The belief is so widespread that these places are highlighted in official travel guides and listed on heritage maps of the island. Visitors are encouraged to explore where enslaved Grenadians purportedly endured unimaginable suffering, the only such sites available from that brutal past.

There is, however, one problem with these places of remembrance (particularly those on the plantations): none actually date to pre-Emancipation times, let alone present evidence that they were ever used to house enslaved people for any reason.

Slave Pens in the History of Atlantic Slavery

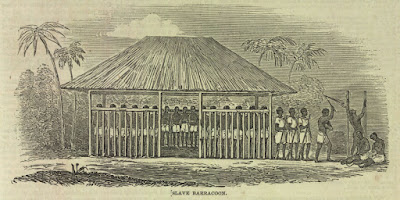

Historically, the slave pen referred to a place for keeping captives confined, especially as a temporary holding facility for enslaved Africans on the West African coast in places like present-day Ghana, Sierra Leone (Figure 3), and Nigeria (Sayer 2021) while awaiting transportation to the Americas across the torturous Middle Passage. The use of the word “pen” is clearly illustrative of the regard and treatment meted out to those it imprisoned. These fenced and thatched sheds or “houses” were also known by the Spanish name barracoon (from Catalan for “hut” via Spanish barracón). It is interesting to note that the appearance in text of the word barracoon dates to circa 1840, but similar structures were widespread during the entire period of the Atlantic Slave Trade.

In North America, a slave pen referred to a building where enslaved who ran away were confined following recapture, for sale or until transportation, the most infamous of which was in Alexandria, Virginia (as depicted in the movie 12 Years a Slave) (Figure 4). In Henry Bibb’s account as a slave in New Orleans, he describes the holding area as a “pen,” which can still be visited today (El-Shafei et al. nd).

In the Caribbean, the early use of the term slave pen was reserved for places on islands like Curacao (by the Dutch) and the British Virgin Islands, which functioned as slave depots where captive Africans were publicly displayed for sale across the region. Though the term was not applied to specific buildings or institutions on plantations during slavery (but may have been used for confinement), several across the region have since been designated as such in attempts to (re)define the relic slave landscape. For example, as part of its Slave Route project, Guadeloupe identified as a place of memory, the “Slave Cell of Belmont Plantation.” According to the brochure, “This is a slave cell from the 18th century, which was used to lock up slaves who had been punished by the master of the estate…. Many plantations had a cell of this type…” (see Slave Cell of Belmont Plantation video and text). Another is at the Annaberg plantation on St John, USVI, where a “dungeon” cell still contains leg shackles and graffiti drawn by enslaved prisoners (Figure 5).

In St Lucia, there is a small stone building attached to the St Lucia Distillery in the Roseau valley and described as having been used as a “slave cell” or prison, one of three designated on the island (Island Resource Foundation 1974). This “slave cell,” which dates to the 18th Century, was “restored” and a sign provided information on its history, adding that it “needs to be preserved for posterity… as a witness to a particular form of human exploitation, …[and] should be declared a preserved national monument….” (see Oasis Marigot nd).

There have been less convincing cases as well. In South Quay, Port of Spain, Trinidad, there was an attempt to designate an old brick vault as a slave cell “to the utter amusement of the older heads of Port-of Spain.... Candlelight vigils began to take place there, processions of hundreds of people assembled in the vacant lot around this forlorn, abandoned structure” (Besson 2011).

Slave Prisons in Grenada

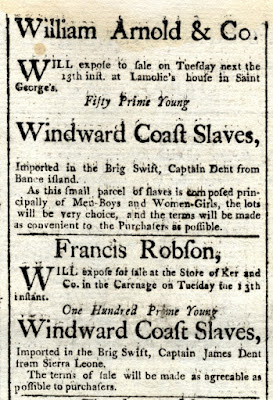

In Grenada, during slavery, the places of confinement were “Slave Yards” for the sale of newly arrived captives, and Public Cages for the incarceration of runaway enslaved or maroons. Slave Yards were located mainly along the Carenage and a few other places in St George’s, where enslaved were held for sale by slave factors or merchants after being unloaded from slave ships; captives were also sold directly off slave ships anchored on the Carenage (see Butterworth 1831). A 1799 newspaper advertisement listed “Lamolie’s House” as a place of sale of captive Africans, which would have been most likely in the present parking lot of the First Caribbean International Bank on Church Street; it also lists the “Store of Ker and Co in the Carenage” (Figure 6), as well as The Long Room (an auction house near Fort George).

Enslaved were sometimes confined in the public jail (on Young Street in what is today known as the Drill Yard), which was primarily for free people (white and non-white), and “The persons confined in the gaol are debtors, criminals, delinquents under the Militia Act, and slaves taken in execution.” More often than not, enslaved were held in Public Cages usually located in the major towns. In 1824, Grenada had four cages (including one in Carriacou) where “…not only are runaways and disorderly slaves confined in these as in other colonies (where the cage is usually and fitly considered to be only a receptacle or lock-up place for the night), but delinquent slaves are sent thither for all sorts of misdemeanors, sometimes for confinement, and sometimes for corporal punishment. In the cage in George Town (sic) [in the Market Square], the slaves confined there have no yard to exercise in…” (Grenada 1832). Enslaved were also confined on plantations in stocks or locally built structures that were mostly of a temporary nature.

Grenada’s “Slave Pens”

Following the US Invasion of Grenada in 1983, the island went through a period of soul searching and re-imagining of its past. While some interest in heritage had begun during the Revolution, the growing tourism industry created a desire for historical narratives of the landscape. Thus, we see the emergence of supposed “slave pens” in the late 1980s as a way to connect the current descendants of enslaved peoples in Grenada with the enslaved landscape of their ancestors. It was the first time in generations that Grenadians had sought to make a physical connection with the enslavement of their ancestors. Few details were provided, except that enslaved were locked in these “pens” when they misbehaved, as a form of punishment. Others envisioned a holding cell, where “new arrivants were quarantined and broken” (Omowale 2007). Some have also been imagined as “breeding cells,” where select males and females were forced to procreate. It is not clear how these structures were “discovered” or the evidence for their use, but word soon spread, and they were accepted as a landmark to their community’s enslaved past, where none had existed before, and representative of the horrors of slavery.

The “slave pen” at Hermitage Estate, St Patrick is the most prominent of the “slave pens” in Grenada. A sign in the area identifies and requests that permission be sought before visiting (Figure 7). Today, it is one of several ruins on the plantation, including the estate house, outdoor kitchen, and remains of cocoa drying trays. The “slave pen” is located just beyond the outbuildings (Figure 8), particularly the kitchen, which is most likely what it was associated with (as a storeroom of some sort). Its proximity, directly in sight of the house, is a major reason in disqualifying it as a place of incarceration of enslaved persons. The existing ruins also date to 1917 (long after slavery), although the foundation goes back to at least the 1770s, when the plantation was owned by James Baillie of Baillie’s Bacolet.

The “slave pen” at Mount Rich Estate is located directly below what was assuredly the kitchen (again supporting its use as a storeroom) (Figure 9). A historical photograph of the estate, showing the location of the “slave pen,” provides further evidence that it was associated with the outdoor kitchen above (Figure 10).

Although the Kent family that built the Mount Rich house arrived during the collapse of the sugar industry in the 1860s, several of their properties have been mistakenly associated with colonial-era slavery. A 2014 commentary in an online Grenada newspaper correlated the so-called effects of the Mount Rich “slave pen” to the high rates of prison incarceration of current residents of the area: “Mount Rich people are victims of white and mulatto oppressors from slavery…. There are many more hidden slave pens in Mount Rich, close to the playing field and the planter’s great house... From the day the Africans were brought to Mount Rich as slaves to work on the Kent’s family estate, they resisted, and by so doing, they encountered harsh prison sentences. The slave pens were prisons built by the Kents to incarcerate slaves who disobeyed” (George 2014). Again, the Kents arrived after slavery had ended.

Lastly, the Melville Street “slave pen” is slightly different from the two plantation structures in that it is part of an old colonial building, probably dating to the late 18th or early 19th Century. Many of these buildings along Melville Street were used as commercial establishments on the lower or street-level floor, with the family living above. Thus, like the others, this “slave pen” was likely a storage area, quite similar to the basements for the other buildings along the street, often used for wines and other spirits that needed cooler temperatures to reduce spoilage. Its designation appears to have arose from an old tale by an elder resident of the town who remembered as a child being told stories of enslaved being kept there. It was also claimed that it connected to the sea through a tunnel and therefore afforded direct import from the slave ships to the “dungeon.” However, this contradicts the first-hand account of William Butterworth (1831), who recalled the Carenage as his first stop after the Middle Passage, as well as the aforementioned places of sale at Lamolie’s House, “Store of Ker and Co” and the Long Room. Evidence suggests, therefore, that any open “pens” would have been on the Carenage, where there was ample space and proximity to shipping.

Within the last few years, the Melville Street “slave pen” has become the focal point for the annual commemoration of Emancipation Day on 1st August, hence the painting that adorns the entrance (Figures 11 & 12). The torch-light parade through the streets of St George’s begins here, following the wreath laying ceremony in the basement dedicated to the memory of ancestors who endured slavery. There was even talk of affixing a plaque to the building, thus designating it a historical monument because of the belief that enslaved Africans once experienced undue horrors there.

If Not “Slave Pens,” Then What?

So if these structures are not “slave pens” as advertised, then what were they? Well, as suggested above, they were storage buildings, either associated with post-Emancipation plantation kitchens (in the case of Mount Rich and Hermitage) or cool, underground storage for merchandise (in the case of Melville Street).

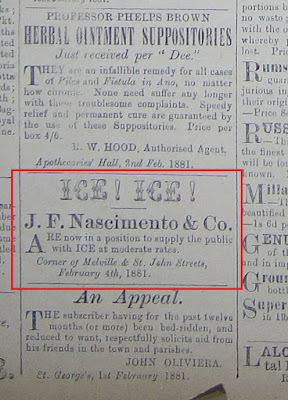

But we can go even further in suggesting that the two structures on the plantations were most likely ice houses, as identified by Andrew Crosby (personal communication) and further researched by the author. As such, they would have been constructed in the mid to late-1800s to store ice imported from North America (through Frederic Tudor, well known as the “Ice King”) that was used to cool drinks and food (even make ice cream) in the absence of electricity for refrigeration (Figures 13 & 14) (see “Frederic Tudor,” Wikipedia).

These two structures bear much resemblance to ice houses prevalent in the UK at that time (e.g., see Google Image search of ice houses in the UK). Some of these features include: proximity to the kitchen (as identified above), a conical roof, “igloo-style doorways for [limited] access,” and a significant portion of the building below ground for insulation (Figures 15,16,17). Both of the plantation structures were constructed of bricks and stones, but the one at Mount Rich is more complex because of its vents and internal demarcation that may have had something to do with drainage. The Mount Rich structure could also have been altered and repurposed, hence its current orientation. Imported ice was a costly luxury, so these ice houses would not have been prevalent in Grenada . It would be worthwhile to explore if any other plantations had similar structures and identify these historic ruins correctly.

An Ending with a Beginning

The goal of this analysis is not to denigrate the myth of Grenada’s “slave pens” (which is a genuine plea to find ancestry in the historical landscape), but to show that there is a great need to directly connect the people of Grenada with their true past while also correctly identifying the historical landscape. That past has to navigate through 185 years of slavery and then 187 years post-Emancipation that shaped both the physical and psychological landscape, yet which seem to tell very little of what we desire to know. As a way to address the situation, I believe that there should be a greater emphasis on historical archaeology to assist descendants of enslaved Africans to connect with their past in a way that provides knowledge of how the enslaved lived, celebrated, cared for their children, resisted, or whatever it is that can be revealed. It is a unique opportunity for archaeology to play an important role in facilitating the dialogue on slavery (as it has already done on a limited basis), and to help many Grenadians begin to construct an identity based on better knowledge of their past. Such knowledge will empower people and connect them to artifacts that they know were part of the lives of their ancestors, thus creating, for the first time, awareness of lives of enslaved that once laid buried deep in the earth. In speaking of the “slave pens,” I believe that archaeological exploration of them would also be valuable to helping answer historical questions.

Unfortunately, archaeology is the only way to identify material remains of our past but is little emphasized in Grenada. In 2016, archaeologists from the Faculty of Archaeology, Leiden University conducted an impact assessment at what is now the La Poterie playing field and its immediate surroundings (Hauser and Hofman 2017). They found artifacts and house floors from enslaved Africans who once lived in the adjoining area east of the playing field, and reasoned that the area should be explored further to at least recover possible archaeological remains. Within a year, however, the field was expanded and no further work on the site occurred. Despite some press about the expansion of the field and the possible impact of the archaeological site, there was not much public outcry. Today, if that site is remembered at all, it is just another story, seemingly no different than any other tale, slave pens or otherwise.

As this example highlights, Grenada’s heritage is more at risk than ever—and it will remain so until archaeology is included in the impact assessments for pending construction. If we do not start valuing what we have, there will not be anything left for our descendants to find in the historical landscape. Do we want our future children to have to go to other islands to understand what their ancestors went through? Do we want to give them something more than Anansi stories? There is much to learn and not much time left, so instead of misinterpreting abandoned structures, we need to get involved, to raise our voices and take action to preserve Grenada’s disregarded heritage.

References

Besson, Gerard. 2011. “Where Slaves Were Hung: Myth Becoming History,” Blog Post, 27 September (accessed 10 November 2021).

Butterworth, William. 1831. Three Years Adventures of a Minor in England, Africa and the West Indies, South Carolina and Georgia. Leeds, Thos. Inchbold.

El-Shafei, Dahlia, Kate Mason, and Kathryn O’Dwyer, editor, “Henry Bibb and The Slave Pens of New Orleans,” New Orleans Historical, Retrieved 21 November 2021.

“Frederic Tudor,” Wikipedia. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

George, Hudson. 2014. Mt Rich. Grenadian Connection.

“Grenada.” 1832. The Eight Report of the Committee of the Society for the Improvement of Prison Discipline, and for the Reformation of Juvenile Offenders, v.3:313

Hauser, Mark W. and Corinne L. Hofman. 2017. “Grenada 2017, Test Pits at the La Poterie Playing Field,” in Hofman et al., Field Report From the Work Carried Out at La Poterie, Grenada in January 2017. Leiden University.

Island Resource Foundation. 1974. “Environmental Survey and Status Report of Selected Caribbean Islands.” Final Draft Report-UNDP-Contract 133/73. USVI.

Martin, John Angus. 2007. A-Z of Grenada Heritage. Oxford: Macmillan Caribbean.

Oasis Marigot. Nd. “Old Slave Cells of St Lucia: A Reminder of the Past,” Retrieved 21 November 2021.

|

| Figure 1. River Antoine estate in St Patrick still producing rum utilizing slavery-era technology in its waterwheel and aqueduct system (courtesy Grenada National Museum) |

The current relic landscape, particularly the plantations, reveals little of its slave past. The most noticeable are the few remaining “estate houses” or ruins that may tell a tale of the slave-owning families who resided there, but most were actually built post-Emancipation, having little or no connection to slavery itself. The decaying windmill towers, copper pots, rusted waterwheels and crumbling aqueducts that fueled centuries of production of sugar seem almost out of place today and little connected to that dark past (Figure 2). That brutal, dehumanizing system of forced and torturous servitude that ended 187 years ago. For the majority of Grenadians, the descendants of the islands’ enslaved, there is nothing in these idyllic, picturesque landscapes that reminds of the suffering their ancestors endured during slavery and that impact their lives even today. It is as if slavery never existed at all, or simply vanished with the changing landscape!

|

| Figure 2. Ruins of the abandoned (since 2004) waterwheel at Dunfermline Estate, St Andrew (photo by Angus Thompson, courtesy the Grenada National Trust) |

But Grenadians have nonetheless found at least three dark corners tucked into the architectural landscape that they have deemed places of significance in the enslavement of their ancestors. On the Hermitage and Mount Rich Plantations in St Patrick and on Melville Street in St George’s, they have identified what have become known as “Slave Pens” where many believe that enslaved Africans were held there for either security, punishment, breeding, or any variety of nefarious purposes. The cavernous and dark nature of these spaces signify to many the depravity of slavery, and have made these places reverential to the memory of brutalized lives. They are akin to tombs of the unknown to countless ancestors who we know so little of beyond a singular name, if at all. The belief is so widespread that these places are highlighted in official travel guides and listed on heritage maps of the island. Visitors are encouraged to explore where enslaved Grenadians purportedly endured unimaginable suffering, the only such sites available from that brutal past.

There is, however, one problem with these places of remembrance (particularly those on the plantations): none actually date to pre-Emancipation times, let alone present evidence that they were ever used to house enslaved people for any reason.

Slave Pens in the History of Atlantic Slavery

Historically, the slave pen referred to a place for keeping captives confined, especially as a temporary holding facility for enslaved Africans on the West African coast in places like present-day Ghana, Sierra Leone (Figure 3), and Nigeria (Sayer 2021) while awaiting transportation to the Americas across the torturous Middle Passage. The use of the word “pen” is clearly illustrative of the regard and treatment meted out to those it imprisoned. These fenced and thatched sheds or “houses” were also known by the Spanish name barracoon (from Catalan for “hut” via Spanish barracón). It is interesting to note that the appearance in text of the word barracoon dates to circa 1840, but similar structures were widespread during the entire period of the Atlantic Slave Trade.

|

| Figure 3. “Slave Barracoon” in Sierra Leone, West Africa, c1840s (courtesy The Illustrated London News, 14 April 1849, v.14:237) |

In North America, a slave pen referred to a building where enslaved who ran away were confined following recapture, for sale or until transportation, the most infamous of which was in Alexandria, Virginia (as depicted in the movie 12 Years a Slave) (Figure 4). In Henry Bibb’s account as a slave in New Orleans, he describes the holding area as a “pen,” which can still be visited today (El-Shafei et al. nd).

|

| Figure 4. The façade of the Alexandria, Virginia, slave pen 1861–1865 (courtesy of Metropolitan Museum of Art) |

In the Caribbean, the early use of the term slave pen was reserved for places on islands like Curacao (by the Dutch) and the British Virgin Islands, which functioned as slave depots where captive Africans were publicly displayed for sale across the region. Though the term was not applied to specific buildings or institutions on plantations during slavery (but may have been used for confinement), several across the region have since been designated as such in attempts to (re)define the relic slave landscape. For example, as part of its Slave Route project, Guadeloupe identified as a place of memory, the “Slave Cell of Belmont Plantation.” According to the brochure, “This is a slave cell from the 18th century, which was used to lock up slaves who had been punished by the master of the estate…. Many plantations had a cell of this type…” (see Slave Cell of Belmont Plantation video and text). Another is at the Annaberg plantation on St John, USVI, where a “dungeon” cell still contains leg shackles and graffiti drawn by enslaved prisoners (Figure 5).

|

| Figure 5. The “dungeon” on the Annaberg plantation, St John, USVI (courtesy B. Mistretta, 2017) |

In St Lucia, there is a small stone building attached to the St Lucia Distillery in the Roseau valley and described as having been used as a “slave cell” or prison, one of three designated on the island (Island Resource Foundation 1974). This “slave cell,” which dates to the 18th Century, was “restored” and a sign provided information on its history, adding that it “needs to be preserved for posterity… as a witness to a particular form of human exploitation, …[and] should be declared a preserved national monument….” (see Oasis Marigot nd).

There have been less convincing cases as well. In South Quay, Port of Spain, Trinidad, there was an attempt to designate an old brick vault as a slave cell “to the utter amusement of the older heads of Port-of Spain.... Candlelight vigils began to take place there, processions of hundreds of people assembled in the vacant lot around this forlorn, abandoned structure” (Besson 2011).

Slave Prisons in Grenada

In Grenada, during slavery, the places of confinement were “Slave Yards” for the sale of newly arrived captives, and Public Cages for the incarceration of runaway enslaved or maroons. Slave Yards were located mainly along the Carenage and a few other places in St George’s, where enslaved were held for sale by slave factors or merchants after being unloaded from slave ships; captives were also sold directly off slave ships anchored on the Carenage (see Butterworth 1831). A 1799 newspaper advertisement listed “Lamolie’s House” as a place of sale of captive Africans, which would have been most likely in the present parking lot of the First Caribbean International Bank on Church Street; it also lists the “Store of Ker and Co in the Carenage” (Figure 6), as well as The Long Room (an auction house near Fort George).

|

| Figure 6. Advertisement for captive Africans in the St George’s Chronicle and Grenada Gazette, 9 August 1799, showing where they were to be sold (courtesy American Antiquarian Society) |

Enslaved were sometimes confined in the public jail (on Young Street in what is today known as the Drill Yard), which was primarily for free people (white and non-white), and “The persons confined in the gaol are debtors, criminals, delinquents under the Militia Act, and slaves taken in execution.” More often than not, enslaved were held in Public Cages usually located in the major towns. In 1824, Grenada had four cages (including one in Carriacou) where “…not only are runaways and disorderly slaves confined in these as in other colonies (where the cage is usually and fitly considered to be only a receptacle or lock-up place for the night), but delinquent slaves are sent thither for all sorts of misdemeanors, sometimes for confinement, and sometimes for corporal punishment. In the cage in George Town (sic) [in the Market Square], the slaves confined there have no yard to exercise in…” (Grenada 1832). Enslaved were also confined on plantations in stocks or locally built structures that were mostly of a temporary nature.

Grenada’s “Slave Pens”

Following the US Invasion of Grenada in 1983, the island went through a period of soul searching and re-imagining of its past. While some interest in heritage had begun during the Revolution, the growing tourism industry created a desire for historical narratives of the landscape. Thus, we see the emergence of supposed “slave pens” in the late 1980s as a way to connect the current descendants of enslaved peoples in Grenada with the enslaved landscape of their ancestors. It was the first time in generations that Grenadians had sought to make a physical connection with the enslavement of their ancestors. Few details were provided, except that enslaved were locked in these “pens” when they misbehaved, as a form of punishment. Others envisioned a holding cell, where “new arrivants were quarantined and broken” (Omowale 2007). Some have also been imagined as “breeding cells,” where select males and females were forced to procreate. It is not clear how these structures were “discovered” or the evidence for their use, but word soon spread, and they were accepted as a landmark to their community’s enslaved past, where none had existed before, and representative of the horrors of slavery.

The “slave pen” at Hermitage Estate, St Patrick is the most prominent of the “slave pens” in Grenada. A sign in the area identifies and requests that permission be sought before visiting (Figure 7). Today, it is one of several ruins on the plantation, including the estate house, outdoor kitchen, and remains of cocoa drying trays. The “slave pen” is located just beyond the outbuildings (Figure 8), particularly the kitchen, which is most likely what it was associated with (as a storeroom of some sort). Its proximity, directly in sight of the house, is a major reason in disqualifying it as a place of incarceration of enslaved persons. The existing ruins also date to 1917 (long after slavery), although the foundation goes back to at least the 1770s, when the plantation was owned by James Baillie of Baillie’s Bacolet.

|

| Figure 7. Sign at the entrance insisting that permission should be had before entering the Hermitage Estate, St Andrew (the Author) |

|

| Figure 8. “Slave Pen” on the Hermitage Estate, St Andrew, showing the partially underground design (photo by Angus Thompson/courtesy the Grenada National Trust) |

The “slave pen” at Mount Rich Estate is located directly below what was assuredly the kitchen (again supporting its use as a storeroom) (Figure 9). A historical photograph of the estate, showing the location of the “slave pen,” provides further evidence that it was associated with the outdoor kitchen above (Figure 10).

|

| Figure 9. “Slave Pen” entrance (in red) on the Mount Rich Estate, St Andrew as part of the foundations of ruins of other buildings (the Author) |

|

| Figure 10. Cocoa pickers with tools on the Mount Rich Estate, St Andrew, c1890, showing building above the “slave pen” (in red) (courtesy Grenada National Museum) |

Although the Kent family that built the Mount Rich house arrived during the collapse of the sugar industry in the 1860s, several of their properties have been mistakenly associated with colonial-era slavery. A 2014 commentary in an online Grenada newspaper correlated the so-called effects of the Mount Rich “slave pen” to the high rates of prison incarceration of current residents of the area: “Mount Rich people are victims of white and mulatto oppressors from slavery…. There are many more hidden slave pens in Mount Rich, close to the playing field and the planter’s great house... From the day the Africans were brought to Mount Rich as slaves to work on the Kent’s family estate, they resisted, and by so doing, they encountered harsh prison sentences. The slave pens were prisons built by the Kents to incarcerate slaves who disobeyed” (George 2014). Again, the Kents arrived after slavery had ended.

Lastly, the Melville Street “slave pen” is slightly different from the two plantation structures in that it is part of an old colonial building, probably dating to the late 18th or early 19th Century. Many of these buildings along Melville Street were used as commercial establishments on the lower or street-level floor, with the family living above. Thus, like the others, this “slave pen” was likely a storage area, quite similar to the basements for the other buildings along the street, often used for wines and other spirits that needed cooler temperatures to reduce spoilage. Its designation appears to have arose from an old tale by an elder resident of the town who remembered as a child being told stories of enslaved being kept there. It was also claimed that it connected to the sea through a tunnel and therefore afforded direct import from the slave ships to the “dungeon.” However, this contradicts the first-hand account of William Butterworth (1831), who recalled the Carenage as his first stop after the Middle Passage, as well as the aforementioned places of sale at Lamolie’s House, “Store of Ker and Co” and the Long Room. Evidence suggests, therefore, that any open “pens” would have been on the Carenage, where there was ample space and proximity to shipping.

Within the last few years, the Melville Street “slave pen” has become the focal point for the annual commemoration of Emancipation Day on 1st August, hence the painting that adorns the entrance (Figures 11 & 12). The torch-light parade through the streets of St George’s begins here, following the wreath laying ceremony in the basement dedicated to the memory of ancestors who endured slavery. There was even talk of affixing a plaque to the building, thus designating it a historical monument because of the belief that enslaved Africans once experienced undue horrors there.

(Note: A similar claim was recently made for ruins on a plantation in Carriacou, but the underground structure was in fact a (water) cistern, several of which can be found on the island where they were used to store water, as the island has no permanent freshwater).

|

| Figure 11. Underground cellar identified as “slave pen” at The Police Barracks on Melville Street, St George’s (the Author) |

|

| Figure 12. Interpretative artwork at the entrance to the “Slave Pen” at The Police Barracks on Melville Street, St George’s (courtesy Roy Wroth) |

If Not “Slave Pens,” Then What?

So if these structures are not “slave pens” as advertised, then what were they? Well, as suggested above, they were storage buildings, either associated with post-Emancipation plantation kitchens (in the case of Mount Rich and Hermitage) or cool, underground storage for merchandise (in the case of Melville Street).

But we can go even further in suggesting that the two structures on the plantations were most likely ice houses, as identified by Andrew Crosby (personal communication) and further researched by the author. As such, they would have been constructed in the mid to late-1800s to store ice imported from North America (through Frederic Tudor, well known as the “Ice King”) that was used to cool drinks and food (even make ice cream) in the absence of electricity for refrigeration (Figures 13 & 14) (see “Frederic Tudor,” Wikipedia).

|

| Figure 13. Enslaved unloading ice in Cuba, 1832 (from A Pictorial Geography of the World by Samuel Griswold Goodrich, 1832) |

|

| Figure 14. Ice advertised for sale in The George’s Chronicle and Grenada Gazette, 12 February 1881, page 1 |

These two structures bear much resemblance to ice houses prevalent in the UK at that time (e.g., see Google Image search of ice houses in the UK). Some of these features include: proximity to the kitchen (as identified above), a conical roof, “igloo-style doorways for [limited] access,” and a significant portion of the building below ground for insulation (Figures 15,16,17). Both of the plantation structures were constructed of bricks and stones, but the one at Mount Rich is more complex because of its vents and internal demarcation that may have had something to do with drainage. The Mount Rich structure could also have been altered and repurposed, hence its current orientation. Imported ice was a costly luxury, so these ice houses would not have been prevalent in Grenada . It would be worthwhile to explore if any other plantations had similar structures and identify these historic ruins correctly.

|

| Figure 15. The “igloo-like” entrance to the “slave pen” on the Hermitage Estate, St Andrew (the Author) |

|

| Figure 16. Looking through the entrance to the “slave pen” on the Hermitage Estate, St Andrew (the Author) |

|

| Figure 17. The interior of the “slave pen” on Mount Rich Estate, St Patrick (the Author) |

An Ending with a Beginning

The goal of this analysis is not to denigrate the myth of Grenada’s “slave pens” (which is a genuine plea to find ancestry in the historical landscape), but to show that there is a great need to directly connect the people of Grenada with their true past while also correctly identifying the historical landscape. That past has to navigate through 185 years of slavery and then 187 years post-Emancipation that shaped both the physical and psychological landscape, yet which seem to tell very little of what we desire to know. As a way to address the situation, I believe that there should be a greater emphasis on historical archaeology to assist descendants of enslaved Africans to connect with their past in a way that provides knowledge of how the enslaved lived, celebrated, cared for their children, resisted, or whatever it is that can be revealed. It is a unique opportunity for archaeology to play an important role in facilitating the dialogue on slavery (as it has already done on a limited basis), and to help many Grenadians begin to construct an identity based on better knowledge of their past. Such knowledge will empower people and connect them to artifacts that they know were part of the lives of their ancestors, thus creating, for the first time, awareness of lives of enslaved that once laid buried deep in the earth. In speaking of the “slave pens,” I believe that archaeological exploration of them would also be valuable to helping answer historical questions.

Unfortunately, archaeology is the only way to identify material remains of our past but is little emphasized in Grenada. In 2016, archaeologists from the Faculty of Archaeology, Leiden University conducted an impact assessment at what is now the La Poterie playing field and its immediate surroundings (Hauser and Hofman 2017). They found artifacts and house floors from enslaved Africans who once lived in the adjoining area east of the playing field, and reasoned that the area should be explored further to at least recover possible archaeological remains. Within a year, however, the field was expanded and no further work on the site occurred. Despite some press about the expansion of the field and the possible impact of the archaeological site, there was not much public outcry. Today, if that site is remembered at all, it is just another story, seemingly no different than any other tale, slave pens or otherwise.

As this example highlights, Grenada’s heritage is more at risk than ever—and it will remain so until archaeology is included in the impact assessments for pending construction. If we do not start valuing what we have, there will not be anything left for our descendants to find in the historical landscape. Do we want our future children to have to go to other islands to understand what their ancestors went through? Do we want to give them something more than Anansi stories? There is much to learn and not much time left, so instead of misinterpreting abandoned structures, we need to get involved, to raise our voices and take action to preserve Grenada’s disregarded heritage.

-John Angus Martin

References

Besson, Gerard. 2011. “Where Slaves Were Hung: Myth Becoming History,” Blog Post, 27 September (accessed 10 November 2021).

Butterworth, William. 1831. Three Years Adventures of a Minor in England, Africa and the West Indies, South Carolina and Georgia. Leeds, Thos. Inchbold.

El-Shafei, Dahlia, Kate Mason, and Kathryn O’Dwyer, editor, “Henry Bibb and The Slave Pens of New Orleans,” New Orleans Historical, Retrieved 21 November 2021.

“Frederic Tudor,” Wikipedia. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

George, Hudson. 2014. Mt Rich. Grenadian Connection.

“Grenada.” 1832. The Eight Report of the Committee of the Society for the Improvement of Prison Discipline, and for the Reformation of Juvenile Offenders, v.3:313

Hauser, Mark W. and Corinne L. Hofman. 2017. “Grenada 2017, Test Pits at the La Poterie Playing Field,” in Hofman et al., Field Report From the Work Carried Out at La Poterie, Grenada in January 2017. Leiden University.

Island Resource Foundation. 1974. “Environmental Survey and Status Report of Selected Caribbean Islands.” Final Draft Report-UNDP-Contract 133/73. USVI.

Martin, John Angus. 2007. A-Z of Grenada Heritage. Oxford: Macmillan Caribbean.

Oasis Marigot. Nd. “Old Slave Cells of St Lucia: A Reminder of the Past,” Retrieved 21 November 2021.

Omowale, David. 2007 “The Experience of the Slave Trade and Slavery: Slave Narratives and the Oral History of Grenada, Carriacou and Petite Martinique, Part 2,” Big Drum Nation online magazine.

Sayer, Faye. 2021. “Localizing the Narrative: The Representation of the Slave Trade and Enslavement Within Nigerian Museums,” Journal of African Diaspora Archaeology and Heritage, DOI: 10.1080/21619441.2021.1963034.

“The Slave Cell of Belmont Plantation, Guadeloupe,” Slavery and Remembrance: A Guide to Sites, Museums and Memory. Retrieved 21 November 2021 at video and text.

Sayer, Faye. 2021. “Localizing the Narrative: The Representation of the Slave Trade and Enslavement Within Nigerian Museums,” Journal of African Diaspora Archaeology and Heritage, DOI: 10.1080/21619441.2021.1963034.

“The Slave Cell of Belmont Plantation, Guadeloupe,” Slavery and Remembrance: A Guide to Sites, Museums and Memory. Retrieved 21 November 2021 at video and text.

Amazing read...in depth research. Thank you.

ReplyDeletethank you!

DeleteWell researched, informative and an educational resource unlike any other I have encountered.

ReplyDeleteHow we get to the next level?🤔

Need to increase readership!

thank you -- good question!

Delete